TALK GIVEN AT THE UKAGP CONFERENCE ON 21ST SEPTEMBER 2014, WESLEY HOTEL, EUSTON, LONDON

By Belinda Harris PhD

Thank you Jacqui, for inviting me on behalf of the UKAGP Committee. I am very aware that I am stepping into highly auspicious shoes, after Guus Klaren’s inspirational keynote last year, and I also need to acknowledge that I am stepping into Jenny McKewn’s shoes because she should have been here today. I’m sorry if some of you are disappointed. It is humbling to stand here, and I am slightly nervous, which is interesting as I’ve spoken in front of thousands of people before but I never knew any of them, so it was easy! Speaking in front of my own community is a different matter altogether.

I’d also like to thank a few other people for today who have given me a lot of support in the run up to this conference when I felt the honourable thing to do would be to run away. Firstly, I’d like to thank Christine for inviting me to join the editorial team of the British Gestalt Journal. I graduated in 1997 and stayed out of the Gestalt community for ten years. Some of the reasons for that may become clearer as I go through this morning’s talk. In brief, I interviewed Sean Gaffney for the journal and he invited me to a ROOTs conference in Hungary to talk about the research underpinning my book for school leaders. Here I met Edwin Nevis, who called me into the Cape Cod community, and I have never looked back. I have enjoyed all my engagement with the Gestalt community and regret the ten years I avoided you all! The reason I avoided you was my own insecurity and sense of difference. I took Gestalt into my role as an educator and applied my gestalt learning in schools. I kept a very small psychotherapy practice on the side but my main passion has been for applying Gestalt out in the world in different ways and I felt I didn’t fit in with the mainstream gestalt community of psychotherapists. Ed Nevis I miss a lot and I wish he was here. I’d also like to thank Katy, Sarah and Kathryn, who are co-members of a gestalt reading group in Nottingham, and who keep me nourished and sane intellectually, socially and emotionally with all the madness I experience sometimes in my role at the University of Nottingham, which is very un-gestalt like and where I seek to use my gestalt understanding to influence and impact the environment.

I’ve only got half an hour which doesn’t feel like a lot for such a big topic. For the first time in my life I’ve written a script. I have never given a talk reading from paper before and I don’t really like it when other people do it because I miss their contact with the environment but I was worried that I would only get through the first two slides and there would be ten more I hadn’t reached because I’d lost my way. I’ll probably move in and out of script but I will be held to time because James will hold up pieces of paper telling me when there are 5 minutes, and two minutes and then STOP, so hopefully I will manage to say everything I want to say.

What I’m going to do is start off with a little intro to me, as I’m guessing most of you won’t have had a clue who I am before you received the e-mail from Jackie. This is to create some ground in terms of my work. Forgive me, it is not meant to be narcissistic but orientating. I’d then like to say something about the field conditions and what I mean by austerity and surviving , and how hard it is to survive at the moment, in my view. Then I’d like to say what I think Gestalt has to offer at this moment in our history and yet why we are so marginalised, and why our offer isn’t being received by the wider community, which really worries me. I think there are some challenges for us in this situation and I am guessing they will be quite contentious. I would then like to draw on my research in education to think of some ways we can move forward and offer some food for thought for the panel discussion. I am very glad that Beatrix, Malcolm, Gianni and Billy are here and sad that Di Hodgson who is also on the panel this afternoon isn’t here because she is stuck on a train. I have great sympathy for her as I was stuck on a train myself yesterday and it took several hours to get here from Nottingham.

I’m going to spend a little time now on what Sonia Nevis and Joe Melnick describe as the ‘intimate’ part of the gestalt cycle, which is the mobilisation of energy and trust building phase, in this case by telling you a little about myself by way of ground for this talk. The most important thing you need to know is that I am a bit of a foodie. I am of Austrian and Hungarian heritage and my main attachment figure was my grandmother, a chef in a spa hotel in Bad Gleichenberg, in the south eastern corner of Austria, and the person I spent my school holidays with.

I started my professional life as a teacher of EFL, and then after my PGCE moved to work for the European Union running young workers exchange programmes across Europe. This involved a language component and placements in industry, and as a young woman in my 20’s the placement element was a nightmare for me. I was ridiculed by managers, whom I called to account for not giving my students educationally enriching experiences. They would challenge my authority by asking me condescendingly, ‘so what do you know about business?’ which was of course, very little.

Eventually, I moved into working in schools in very deprived communities, firstly in London and then in the East Midlands. What I realised at that point was that despite excellent pedagogical training nothing had prepared me for this work. I was out of my depth. I had no idea how to relate to these very traumatised kids who had no resources in the community and no resources at home, and I was charged with teaching them German and French! Most of them didn’t speak English because they were immigrants, many of them refugees, and housed in such a way as to keep them separate from the rest of the population. Once more I found myself struggling professionally, so I went into person-centred counselling training, which was incredibly helpful in helping me build more effective relationships with kids and their families and some degree of trust. I have a lot of respect for Carl Rogers and his contribution to counselling theory and practice. However, as I moved up through the school hierarchy into senior leadership where I became responsible for pastoral care, I became increasingly aware that my person-centred training hadn’t given me enough and I looked for something else. I had studied in Berlin, and on hearing that gestalt fundamentals originated in Berlin I decided to start Gestalt psychotherapy training. Everything I learned I took back into school with me and it was a really empowering experience. However, I kept my learning quiet. Then we had an Ofsted inspection, a process where schools are inspected by people who come and observe lessons and an inspector was interviewing me in my office when somebody brought me a very distraught, angry boy ‘to deal with’. He walked out of the office ten minutes later much calmer:

Inspector: ‘Where did you learn to do that? How did you do that?’

Belinda: ‘What?’

Inspector: ‘Didn’t you see the change in him?’

Belinda: I just helped him to move through the Gestalt cycle

Inspector: ‘What’s that?’

Everyone in this room in the same situation would have done the same as I had: respond in the moment to where the client is, make contact, help them regulate and become present, mobilise and move towards completion. For the inspector that process was powerful and he mentioned it in the school inspection report, which legitimated my work and gave me the confidence to bring Gestalt into my work more overtly. Much of my time was then spent on teacher development. We then brought the parents in and taught them Gestalt and then I moved to working with staff in other schools, which led me onto a PhD at the University of Nottingham. For the past 20 years I have worked at the University where I have been able to reach a national network of schools and teachers, and have specialised in supporting head teachers to develop humane, relationally oriented professional learning communities. So you can tell that my passion is for applying Gestalt to all aspects of my work (and life). This is my official University photograph, these are colleagues on a recent development day thinking about how to teach reflective practice, and this is one of their creative products. This is a school leader here on a commonwealth scholarship, and with her permission her sandtray from a coaching session we had together.

Moving on to thinking about enriching our community it seems fitting to begin with some consideration of the wider field we are all working in. Some of you may remember this quote which publicized the UKCP conference back in 2006.

This really spoke to me at the time, and helped me with a book I was writing for school principals. I was struck by how little has changed since Jeremiah Whitaker spoke so eloquently in the

Houses of Parliament in 1743, and this notion of shaking has really helped me make links with school leaders and engage teachers in talking about some of the difficult issues they face daily in their working life.

Looking at this list of ‘shakers’ it is easy to think of examples: the referendum in Scotland last week, instability in the Ukraine and wars in the Middle East; natural disasters such as hurricane Odile off the coast of Mexico on Friday; the relentless pressure caused by globalisation and the impact on national economies and the pace of change, and finally how nothing seems to stay still and we are constantly running to catch up with events and with ourselves. So, how do these field conditions impact our working lives, whether in health services, education, industry or business? Just notice how the language has changed over the past twenty years.

I don’t think I need to explain the words on the slide they will be very familiar. Capra distinguished between Life enhancing and Life destroying organisations, and certainly when I started at the University of Nottingham I was in a life-enhancing environment and now I am in one where it is much harder to feel that or to create the conditions within which people feel that. I am struck by how my own research in schools and children’s services has led me to concur with my colleague Chris Watkins at the Institute of Education here in London, whose research in the early 1990’s led him to the conclusion that schools had become ‘frightened organisations’, and I don’t think it’s just schools. A lot of organisations have become incredibly frightened, and the public naming and shaming of schools, social services, hospitals and now GP surgeries in the UK has made this situation worse. We live in a climate that is driven by positioning in the league tables, which puts immense pressure on outcomes (and the choice of outcome measures). The stated aim of improving service quality takes no account of the human cost involved for professionals. Several of my gestalt supervisees are on contracts where they are paid by results, and performance related pay is a euphemism for keeping wages low. In public services therapeutic sessions are framed by completion of some assessment tool, such as the PHQ, CORE or Beck’s Depression Inventory, and evidence of effectiveness is judged by a positive change in score. This is the container for our relational work. Also, session times are being cut, so the 50 minute hour can become 40 minutes, half an hour, or less. In some schools young people are allocated 15 minutes, so that by the time you have completed the two questionnaires there is little time left for the work. However, I keep going back to that time when the inspector sat in and remind myself of what is possible in ten minutes, and that, as Gaie Houston said, we can make a difference in a short period of time. I am also aware that collecting data re effectiveness is important for us as a modality. We might not be able to help someone to move though a complete cycle but we can help them feel better when they walk out of the room through the quality of contact that we can offer, that has a very special and unique quality to it.

So in brief, it is a very ‘One size fits all’ time we are living in, which is not compatible with our focus on relationally attuning to where the client is in their situation. The thing that really annoys me about the whole payment by results culture is that some of my supervisees are only paid if their clients’ scores go up. So, what does that mean? What of those clients who need to go into the creative void and who get worse before they get better? What about all those people who need a lot of time to arrive in their bodies, where there’s no movement at all for ages and ages, and then suddenly mobilise? In the current climate of austerity there is little room for the actual individual in this process, unless they can afford to pay for private sessions.

In reality many people are living in what is commonly called ‘Breadline Britain’ in the press. A Step Change Charity report earlier this year indicated that hard working middle class families earning £35K per annum are on the edge of financial meltdown, with the steepest rise in debt being in the home counties of Surrey and Berkshire, which for those of you not based in England are traditionally more privileged areas. Patrick Butler, social affairs editor at the Guardian has a very informative blog on austerity and in a recent talk he gave in Nottingham claimed that hard working lower middle class families are living on slender margins. Once they have paid their rent and household bills, they are lucky if they have £10 to spend on food to feed the whole family. I think that is a really sobering statistic, so what happens is that parents feed their children before they feed themselves , or they go to work on an empty stomach. They have to make very hard choices. In 2013 900,000 people in England were reliant on food banks and payday loans were the order of the day. That statistic has gone up by 70% this year already. Whether at work or at home, many people feel more like an ‘It’ than a human being. This attitude is embedded in the performativity culture and field conditions that we live with and battle against. Last year Guus talked of this ‘undermining the dignity of the human being’ and hence the universal declaration of human rights – I couldn’t agree more.

Over a century ago Pierre Janet noted that:

TRAUMA PRODUCES ITS DISINTEGRATING EFFECTS ACCORDING TO ITS INTENSITY, DURATION AND REPETITION.

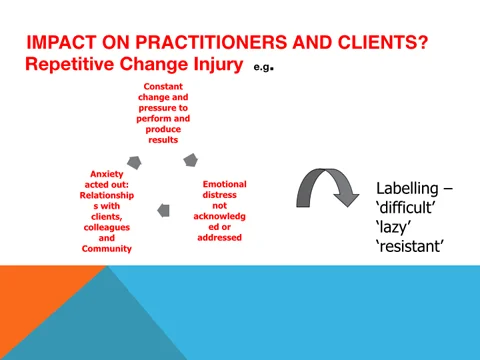

Living on the breadline is traumatic for many families and communities. If I go into schools and use the term trauma however, I find teachers and school leaders unreceptive: ‘we don’t have any school shootings here’, so I have found it helpful to reframe trauma as RCI, Repetitive Change Injury, which they seem to identify with. I discuss with them how RCI has affected teachers. I hear them talking about ‘difficult’, ‘lazy’ teachers because there is no room in the school for their emotional distress to be acknowledged or worked with, and it is therefore acted out through their relationships with pupils, colleagues and parents, or acted in through self-harming behaviours or depression.

I have similar RCI cycles as stimuli for children and parents, and have found this a practical means of helping people acknowledge ‘what is’, and also a powerful way of finding a common language across stakeholders and different professional groupings. This process is of course, also reflected in our own community, which is why it is more important than ever to enrich the community, so that individual practitioners can support others well.

Very briefly I chose these concepts based on feedback from my therapy clients, from the teachers and leaders I work with in schools, and from the staff in my department at the University.

Gestalt’s focus on the person-environment relationship is in my experience a huge relief to clients, who feel met as a whole person situated within their dynamic social context. Our training supports us to find creative ways of joining with others, to attune to the space ‘between’ and to move towards the other with sensitivity and clarity. By noticing emergent figures and patterns we can engage the client’s interest, and I treasure the overt refusal to collude with ‘aboutism’. Personally, I like the concept of ‘dynamic dysequilibrium’ by Bruce Joyce, an educational theorist, who highlights the importance of struggle for deep learning and growth. Gestalt practitioners focus on their own and their client’s embodied experiencing and ‘here and now’ emotions, and capacity to support the client to sit with the reality of ‘what is’ without trying to fix anything is also a huge asset in this process.

Quinn said that ‘Our greatest joy, no matter our role, comes from creating. In that process, people become aware that they were able to do things they once thought were impossible. They have empowered themselves, which in turn empowers those with whom they interact’. Gestalt practitioners know how to co-create, and that distinguishes us from many others. At GISC on Cape Cod I really understood the power of PRESENCE in gestalt practice, and how important it is to be fully available (Here temporally), to be Expressive in my vocal variety and physical communication, to be Authentic, congruent, so that what you see is what you get, to be Rooted present spiritually and grounded , and to be Trust-oriented, both in terms of trusting the unfolding process and also trustworthy – doing everything with awareness and Intentionality, and lining up internally with a goal. I love Archie Roberts mnemonic HEART for presence. Finally, Gestalt practitioners are also integrative and responsive to new developments in the field, such as EMDR, Sensorimotor therapy and Mindfulness.

However, a key concern that I have is whether gestalt can survive within these field conditions. I am essentially an optimist so I believe we can but I do think we need to acknowledge where we are and the challenges facing us as a community.

Firstly I am aware that I see gestalt practice in many other therapies, such as mindfulness training and sensorimotor therapy. In the journal Person-Centred & Experiential Psychotherapies (PCEP) recent papers focus on the ‘Thou-I’ dialogic relationship, and also on the relationship between the social context, the client and power relationships. Gestalt is an experiential therapy and yet there are very few (i.e. none that I have found) references to Gestalt as an influence on thinking or on practice. We have a legacy that doesn’t always serve us well, and makes it easy to dismiss us as a relational therapy. The Gestalt relational turn hasn’t hit the high street yet! I enjoy watching Perls’ work and learn a lot, and I also understand why people without a field-theoretical perspective find the videos and CDs off-putting.

There’s something about our marginal standing in public services that we have also co-created by not standing up and standing out. For example, I recently wrote a chapter on Gestalt for a new handbook on counselling children and young people. Feedback from the editors and reviewers indicated surprise that Gestalt has such a strong evidence base. People are impressed when we put the evidence together but we tend either not to put it together systematically, or not to publish in mainstream journals. We have for example, some powerful CORE data produced by a Practice-based Research Network but no-one else knows about it but us! This doesn’t serve us well. Comparatively, we are under-represented in the mainstream literature. Good on Miriam Taylor and Georges Wollants for publishing with Sage. Good on you Malcolm for writing your new book for a wider audience. I’m looking forward to the time when this is also taken on by a major publisher. There was an interesting discussion on GISCmail recently when gestalt practitioners were omitted from a UKCP survey. How might we be contributing to this? I wonder sometimes if we may be too inward facing and removed from what’s happening in our regional and national professional bodies. I am also aware that our training programmes are very rigorous, and demand a lot from trainees. And yet there are many gestalt trainees in limbo and unable to graduate – what is that about? This was a big theme at the GPTI community meeting earlier this year which seemed to suggest there might be a lack of coordination and shared understanding between supervisors, training supervisory members and examiners. As an academic working in a top UK University, we expect our students to complete and have a 98% completion rate on our counselling training. I am therefore left with many unanswered questions about the moderation and training processes involved for examiners. Until such issues are addressed, there may be a lot of trainees and ex trainees whose commitment to gestalt and confidence in their capacity to practice has been undermined at the final hurdle. In my view, it is most important that new graduates are ‘good enough’ practitioners, sufficiently confident and committed to Gestalt practice to embark on their own professional journey towards mastery, through further direct experience of client work, ongoing supervision, regular CPD and participation in events such as this.

In his TED talk, Seth Godin identifies a range of strategies for getting your ideas to spread. From my own research in education I have identified three processes which I hope will be useful for enriching our community. The first of these is developing relational fitness. What does this mean? Well it involves creating enough psychological safety for people to listen and reconsider their basic assumptions about one another. It is a means to develop awareness and trust between members of a community, and create spaces where we can return to explore the purposes and values underpinning psychotherapy in general, or mental health services in particular, and to revision what our member organisations want and what will best serve the community. I witnessed this in action at the GPTI residential earlier this year, and am reminded of the value and importance of opportunities like this one today. Equally, our virtual communities might play a key role in helping practitioners to engage and embrace our rich diversity of opinions. With enough spaces for everyone to join in and be responded to, individuals can begin to relish the interconnections and understand the intersections embedded in our multiple identities. Such a rich experiential field strengthens our capacity to develop relationships with other practitioners. I know for example, that many experiences of processing and working collaboratively at GISC on Cape Cod gave me the courage to take up a senior leadership role in my workplace, knowing that I had the support and love of a whole community behind me, a community I regularly return to for mentoring, training and friendship.

The second process which builds on relational fitness, is relational maintenance and depth. Here organisational members have multiple opportunities for respectful dialogue and for ‘moving towards the danger’( Maurer, 1995), by deepening the quality of contact, and developing each member’s capacity for the dance of dialogue, so that contact is immediate, vibrant and ‘the mirror in which we see ourselves as we are’ (Krishnamurti). This in turn can encourage greater confidence to be citizens in our professional networks and places of work, rather than tourists travelling through and seeing what we can take from the situation. Sonia Nevis talks potently of asking ourselves regularly what we can give rather than asking what the situation can give us, and sees this shift in emphasis as one sign of a thriving community. At the beginning of this talk I mentioned my reading group, which recently revisited Perls, Hefferline and Goodman, but I also want to mention peer supervision, which gives me a day a month working with four amazing practitioners from different parts of the UK, and where I have learned so much. High quality CPD and practice based research networks are other examples of ways in which we can deepen and expand our connections and our understanding of what is possible.

In my research in schools, I found that when relational fitness and relational maintenance and depth are combined, the third process to arise spontaneously from the field conditions is relational alchemy. This is where stakeholders become bolder and more creative in their interactions with each other and within their sphere of influence, and harness their energy to influence and make an impact on the field. The ‘aliveness’ (Capra, 2003) that is palpable in these interactions encourages others to ‘join’ and work collaboratively in search of new awareness and knowledge creation. Examples of such work might be running an experiential training session for colleagues at work, or creating new gestalt resources, such as DVDs for counselling or psychotherapy training and mainstream distribution, as well as enhancing our profile in some of the more generic counselling and therapy journals.

When we can work with colleagues within and beyond our community to move away from ‘I-It’ relations with each other and with the processes of learning and towards more co-creative, participative, ‘I-Thou’ modes of relating and being, then it is my belief that our shared humanity and leadership can enhance the energy, internal motivation and capacity of embrace change and face difficulties together. Thank you. Thanks also to Deb Lane from GISC who read the original paper ‘Leading By Heart’ and who helped me to recognise the relevance of the data and analytic categories for our contemporary situation.