Christine Stevens, Jane Stringfellow, Katy Wakelin and Judith Waring

Received 5 August 2011

Introduction

This is the account of a three-year research project within the Gestalt therapy community in the UK. It is an example of clinically-based mostly quantitative research carried out in a methodical and rigorous way, using voluntary effort and minimum funding. The results can be compared with national data bases of similar UK studies and show that Gestalt psychotherapists are as effective as therapists trained in other modalities working in the NHS and in primary care.

Background

Gestalt-trained therapists in the UK work in private practice and in the voluntary sector as well as in psychological therapy and counselling services funded by the NHS. Those in NHS posts, however, are often employed for their background in psychiatric nursing or psychology, rather than their professionally accredited Gestalt psychotherapy training. The government-funded IAPT (Improving Access to Psychological Therapies) initiative which has been rolled out to provide counselling in primary care following the Lanyard Report in 2007 has explicitly favoured a Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) approach on the basis that it has a bigger evidence base.

This method of therapy has had the most exposure to clinical trials, since it uses set protocols which enable standardised collection of quantifiable data. It is therefore more able to meet the National Institute for Clinical Evidence (NICE) guidelines for an evidence base, which regards clinical trials as the gold standard in a hierarchy of research methods. Therapies which rely more on the relational process between client and therapist are less suited to this research method and therefore appear to have less of an evidence base according to NICE criteria.

Most Gestalt psychotherapy training in the UK takes place in private institutes and although many of these have validating partnerships with universities, they do not have access to university research funding. This results in training that is strong in clinical methods and practice skills, but with fewer resources for higher level clinical research and correspondingly fewer papers published in this area. Research that is undertaken tends to be small-scale in depth case-studies which are useful for developing skills and understanding of process, but of limited application in the wider field, and do not address outcome issues, for which larger samples and validated measurement tools are required. Many Gestalt therapists, however, do wish to work in the statutory services alongside colleagues trained in other psychotherapeutic modalities, and Gestalt therapists, whatever sector they work in, are ethically concerned with the challenge to be accountable for the quality and standard of their work and to be able to satisfactorily evaluate the effectiveness of what they do.

During 2007, Gestalt therapists’ concern to find a way to research the effectiveness of their work came to a head on the discussion list hosted by GPTI (Gestalt Psychotherapy Training Institute, one of the largest professional membership groups for Gestalt therapists in the UK). One discussant, Jane Stringfellow, volunteered to co-ordinate a project that led to the decision to use CORE, a well-established outcome measure, as a way of collecting data about the work of Gestalt therapists in such a way that it could be compared with data collected from other therapy approaches, including CBT.

CORE

The CORE (Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation) system is now the most widely used approach for audit, evaluation and outcome measurement for psychological therapy and counselling services in the UK. It was developed from 1995-1998 in the Psychological Therapies Research Centre at the University of Leeds by a multi-disciplinary team of researchers and therapists, and became a self-financing initiative in 1998. The CORE National Research Database currently holds data for about 50,000 clients.

The details of the development and application of CORE have been discussed in detail elsewhere (Barkham et al. 2006). To summarise, the system is basically a self-report questionnaire filled in by the client at the beginning and end of therapy, on how they have felt over the past week; and assessment and end of therapy forms completed by the therapist. The 34 items measured cover four dimensions: subjective well-being, problems or symptoms, life functioning and risk or harm. The scores from the questionnaire are averaged to give a mean score to indicate current levels of psychological distress from “healthy” to “severe”. The comparison of pre and post scores offers a measure of outcome – whether the level of distress has changed – and by how much. The system is designed to be completed for each client by each practitioner in a service, thus providing comprehensive profiling rather than selecting only the clients likely to do well.

The CORE measurement is primarily designed to provide managers and practitioners with evidence of service quality and effectiveness. It is not specifically Gestalt orientated; indeed in the list of possible types of therapy in the end of therapy form for the practitioner, there is no box to specify Gestalt apart from “other”. However the decision was made to use this system as it is the most widely used across psychological therapy services on a national level. Many Gestalt therapists working within NHS teams already contribute data in this way, but their Gestalt identity is subsumed within the team as a whole in these settings. What was different about this particular project would be that the data would be collected by Gestalt therapists across workplace contexts, to include public sector, voluntary and private practice.

The Research Project

One of the challenges of this project has been to plan and co-ordinate a medium scale research enterprise using voluntary effort and relying on the professional interest and motivation of members of the Gestalt community. A steering group of six people was formed and information disseminated via the GPTI online list. John Mellor-Clark, one of the developers of the CORE system attended the GPTI conference in June 2007 and gave a presentation to delegates, and a training day was held in November in Birmingham attended by over 30 therapists interested in participating in the research project. A Gestalt Practice Research Network was formed to support the project, with an on-line group to share information among the participants. The GPTI Executive Committee agreed to fund the CORE software licence and inputter training costs for the first year to get the project set up. About 40 Gestalt therapists registered with the project and agreed to send in data sets. A member of the group, Ros Gilham, developed the coding to collect data about the therapists’ work context and experience level, and the software was installed in Christine Stevens’ office in Nottingham, where the completed hard copy sets of data were gradually collected. Periodically over the three year collection period, volunteers, including Jane Stringfellow, Judith Waring, Ros Gilham, Carole Ashton and others met to enter the data sets into the data base using the computer software. A review of the data collected to that point and instructions on its analysis was facilitated by a visit from a CORE representative, Bill Andrews, in November 2009. A presentation was made at the UKAGT conference in June 2009 by Christine Stevens and Judith Waring. At that stage 105 data sets had been input. In June 2010, we stopped collecting data. We had collected information on 249 clients, of which 180 were complete data sets that we could use for analysis. The reason for this difference was because participants were asked to send in data for all their clients during the collection period, not selected ones. This meant that some clients only came once, or ended suddenly so that the end of therapy form could not be collected. Some of the total (10.4%) not included in the analysis is accounted for by long term client work which had not been completed by the end of the study. Other reasons for sets not being complete included the therapist omitting to administer the end of therapy form through forgetting, or for some other reason. Both pre and post CORE scores are needed to measure outcome. In terms of the data sets collected, about 50% of the participating therapists were advanced students on placement in a primary care setting, and they provided 25% of the useable data sets.

The information collected in the research study can be used in two main ways, first to describe some aspects of the client population, and secondly to compare the findings in this study with results from other published studies.

Data Description

It is important to note that most of the clients, just over 70%, seen in this study, were referred by GPs and probably mainly seen by therapists practising in primary care teams. The next largest source of referral, nearly 14% was self referral, perhaps more usual for private practice, and others were referred by another therapist (7.3%), family member or friend (3.2%), psychiatrist, (1.9%), or education-based service (1.2%). About 70% of the clients seen were women, and they were predominantly white British or European (90.4%). Just under a third of the clients were living with children, and 24% lived alone while 34% were living with a partner.

In terms of age, the biggest group of clients in this study were in their 30’s (31%), followed by those in their 40’s (27.3%). More clients in their 20’s (18.9%) were seen than those in their 50’s (12.4%) and after 59 the percentage drops off to 8.8%.

Most clients, about 83% were seen weekly, and 91% of planned sessions were attended.

The CORE Therapist assessment form has categories for the therapist to record the problems the client presents with at assessment. These are given in the table below for this study. The therapist can as many of these categories that apply. This spread of problems is typical for clients referred in primary care and reflects the fact that the majority of Gestalt therapy recorded in this study took place in this context.

Comparative results

Another way to use the CORE data collected is to compare the average over the 34 questions before and after therapy. The lower the score for an individual, the higher the client’s self-classified well being, with fewer symptoms, better life functioning and lower risk of harm. By comparing the score at the beginning and end of therapy we can see if clients classified themselves as doing better on those four criteria following therapy.

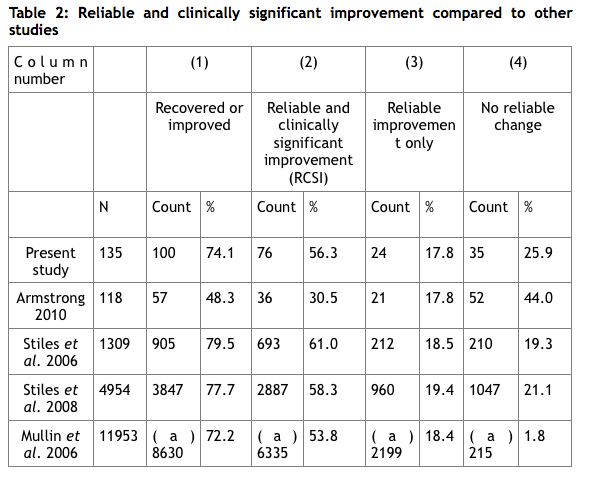

In addition to seeing if the clients classify themselves as doing better in our sample, we can also compare the outcomes measured in this study with those for other studies. The results from three papers are used in Tables 1 and 2 as comparisons to the Gestalt sample used in this paper. By using very large data sets, two of these papers – Stiles et al. (2006, 2008) and Mullin et al. (2006) – provide benchmarks against which other services and practitioners can compare themselves. The first two compare the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural, person-centred and psychodynamic therapies in primary care and NHS settings using the CORE measures. They find that theoretically different approaches appear to have equivalent outcomes – this is known as the equivalence paradox: treatments that have different and incompatible theoretical backgrounds, philosophies and techniques tend to have the same degree of success as measured by CORE. The Mullin et al. (2006) paper aims to provide benchmark results for a large sample of clients who have filled in the CORE papers. The clients were seen in primary care by a variety of therapists and for a variety of reasons. The authors used as broad a sample as possible in order to set benchmarks that can be used for comparison by other studies.

Table 1 shows the mean (average) score over the 34 questions asked by the CORE survey both before and after therapy. Before therapy the average score was 18.3, this is a little higher than the average score in the main benchmarking study of 17.5 and higher than the two comparison studies of 17.4 and 17.6. What this means is that, on average, the clients seen in this Gestalt study appear to be more distressed than those being seen in comparable studies, although we should not make too much of this slight difference as it is within one standard deviation (7.4).

After therapy, the average scores declined to 9.9 for the Gestalt study showing a slightly smaller fall than the comparison studies and the benchmark study. The pre-post difference is the difference between the before and after CORE measures at 8.4 this is comparable to 8.8 and 8.9 in the comparison studies for CBT, person-centred therapy and psychodynamic therapy and to the benchmark result of 8.4. Gestalt appears to be as effective as other modalities using the CORE method of assessment.

(a) information not given

The effect of therapy is measured by effect size. Effect size is given by the mean of the difference between pre-counselling and post-counselling scores over the pre-counselling standard deviation. This is slightly lower in our Gestalt study than the other comparison studies with the exception of Armstrong (2010) where unqualified personnel were used as therapists. Nevertheless, keeping in mind that in this study around a quarter of the data were generated by practitioners who had not completed their training, the effect size is still broadly comparable at 1.12 to the other effect sizes of 1.36, 1.39 and 1.42.

Core Outcome Data

There are additional standard measures used in the CORE literature to assess the effectiveness of therapy. Two measures of improvement are reported in Table 2, they are:

- Reliable improvement – defined as a decrease (i.e. improvement) in the CORE outcome measure score of 5 points or more. This measure was developed to show change that is large enough so that “we can reasonably discard the alternative explanations that this could have happened by chance” (p. 69, Mullin et al., 2006). Some of these will also show clinical improvement (see below) “only improvement” gives those clients that show reliable improvement but not clinical improvement.

- Reliable and clinically significant improvement (RCSI) – defined as a decrease in the CORE outcome measure score of 5 points or more (as above) AND movement from the clinical (above 10) to the non-clinical (below 10) population. This means that the client now looks as if they belong to the general population rather than to the ‘clinical’ population of those people normally entering psychotherapy services. Crudely put they can now be considered ‘recovered’.

- Both counts are included in column (1) to show the overall percentage of clients that showed improvement. For this Gestalt study that is 74.1% or around three quarters of the clients.

- Another potential category is reliable deterioration i.e. a CORE final score five points higher than the start. While some clients did deteriorate in the sample, no clients fitted this category of reliable deterioration.

Only clients for which both pre and post CORE scores were available were included, leaving 135 clients. Other studies’ results were included for comparison. In Table 2 the average improvement rates from Stiles et al. are given across modalities as there did not appear to be significant differences between modalities. As you can see from Table 2, the result for Gestalt therapists – with 56.3% showing reliable and clinically-significant results - appears to be similar to those for the benchmark studies with 53%, 58,3% and 61.0%.

A fourth study was also included. The result from Armstrong (2010) shows a much lower level of RCSI at 30.5%. The explanation for those low CORE figures is that they represent the outcome when using minimally trained/experienced volunteer mental health counsellors. The paper concludes that: “the overall effect of counselling was roughly half of that achieved by professional therapists in the benchmark studies” (p.27, Armstrong, 2010), they also appear to be considerably less effective than the present sample of Gestalt therapists, some of whom are trainees.

In this sample, approximately 74% show recovery or improvement, 56% achieved reliable and clinically-significant improvement, over half the sample and around 18% achieved just reliable improvement alone. Approximately 26% of the sample, just over a quarter, experienced no reliable change. The closest comparisons are probably with the Stiles et al. (2008) as they looked at therapists working in primary care, a similar sample to the one used here and Mullin et al. (2006), which established the CORE outcome measure benchmarks in relation to brief counselling in primary care settings. In those studies approximately 78% and 72% showed recovery or improvement – comparable to the 74% for our sample of Gestalt therapists.

(a) not provided in Mullin et al. (2006), numbers author’s own calculation

Overall, the results support the equivalence paradox found elsewhere in the literature (Stiles et al. 2006, 2008): Gestalt therapists appear to be as effective as other therapists working in primary care.

Afterword

This has been an innovative experiment using low-cost methods by a well-motivated community of Gestalt therapists, showing that collaborative research projects can be undertaken in this way. Research is not just something other people do, but an activity that as practitioners we can all be involved in. Even so, there have been difficulties. Motivation is hard to sustain over time, and there are limits to what busy practitioners can sustain on a voluntary basis. Researching real world activity as it happens requires academic rigour and accurate and consistent data collection. This boils down to the often tedious chore of careful form filling and the collating sending in of data sets, ensuring they are as complete as possible. For therapists trained in relational skills who enjoy the richly textured nuances of contact with others in their daily work, this additional requirement can seem antithetical to what they feel their work is all about.

There are always issues with the research methods, for example, some of us would argue that clients who gain significant awareness through work at relational depth may feel worse in their last week of therapy than they did at the beginning despite being in a more functional life-space. Yet the reality is that we cannot be complacent about issues of public accountability and demonstrable effectiveness. If as Gestalt therapists we do not take seriously the challenge to articulate and evaluate our therapeutic claims, we may be left talking only amongst ourselves and limited to working only with those clients who can afford to pay privately (Stevens 2008 p.315).

We chose to use the CORE system because it is the most widely used outcome evaluation measure currently used in the UK, and some Gestalt therapists already use it in their work places. What our study shows is that when this measure is used on work done exclusively by Gestalt-trained therapists, the results are very similar to other modalities the system codes for, person-centred, cognitive behavioural therapy and psychodynamic approaches. In fact this is consistent with what CORE has shown over the years it has been running, although it has also shown that the outcome difference between individual therapists can be as much as a factor of 10. It may be then that having established an evidence base for Gestalt as a therapeutic modality, we might go on to ask “how can I become a more effective Gestalt therapist?”

1 The Mullin et al (2006) benchmark study uses 5 as the criteria to measure reliable change as in this paper. Both the Stiles et al (2006, 2008) use a figure of 4.8. This is unlikely to have a large impact on the results.

2 Only clients who had filled in at least 30 of the 34 measures are considered to be ‘valid’ outcome measures. In addition, we do not include those clients whose pre-therapy scores were below 10 as they could not, by definition, achieve clinically significant improvement see Stiles et al. (2006, 2008).

The authors would like to thank all those who participated in the Gestalt CORE research project in whatever capacity. We gratefully acknowledge three year’s grant funding from GPTI. Our thanks to the CORE team for their help and support.

In memoriam Ros Gilham who gave generously of her energy and enthusiasm in setting up this project and who sadly died before it was completed.

References

Armstrong, Joe (2010) How effective are minimally trained/experienced volunteer mental health counsellors? Evaulation of CORE outcome data, Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 10(1), pp. 22-31

Barkham, Michael, Mellor-Clark, John, Connell, Janice and Cahill, Jane (2006) A core approach to practice-based evidence: A brief history of the origins and applications of the CORE-OM and CORE System, Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 6 (1) pp. 3-15.

CORE [http//www.coreims.co.uk/index.php?name=EZCMS&page_id=39&menu=504] accessed 5.8.11

Stevens, Christine (2008) Can CORE measure the effectiveness of Gestalt Therapy? In Brownell. Philip (ed) Handbook for Theory, Research and Practice in Gestalt Therapy. Newcastle, Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Stiles, William B., Michael Barkham, John Mellor-Clark and Janice Connell (2008) Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural, person-centred, and psychodynamic therapies in UK primary-care routine practice: replication in a larger sample, Psychological Medicine, 38, pp. 677-688.

Stiles, William B., Michael Barkham, Elspeth Twigg, John Mellor-Clark and Mick Cooper (2006) Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural, person-centred and psychodynamic therapies as practised in UK National Health Service settings, Psychological Medicine, 36, pp. 555-566.